Short Treatise on Arabic Music

Middle East musical art is perhaps what immediately occurs in the collective imagination, as soon as the mind turns to the east. The atmospheres heated by the sun and the sand of the desert seem to convey melodies that recall a culture so different and that, like all those existing in the terrestrial globe, has used the musical medium as its first means of expression. As is well known, peoples have always preferred to sing first than to act, just as they have chosen to remember and hand down by heart rather than write and disseminate. Perhaps for logistical reasons (the lack of media to write on), perhaps by instinct the archaic cultures have entrusted their memory to collective memory rather than to tangible signs that avoided oblivion.

Pre-Islamic Arab culture

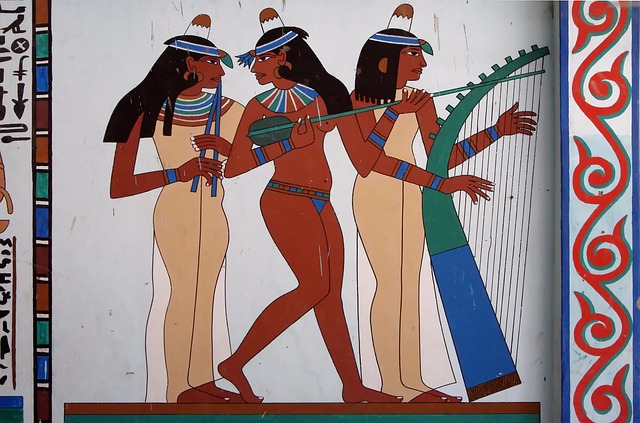

The pre-Islamic Arab culture or known as “of the Jahiliyya” that is Ignorance from the word of God, so called by Muslim scholars in stark contrast to the revelation of the prophet Muhammad, is known precisely through musical testimonies, so to speak. The first literary attestations of the Arab heritage, geographically to be positioned in the Jazirat al Arab, the peninsula of the Arabs (the current Arab peninsula) in a time beginning around 500 AD, are sometimes very long texts in poetry, already endowed with a metric and a certain stylistic rigor.

Among these stand out the “hanging”, the Mu’allaqat, the 7 compositions of as many professional poets, selected for their particular and rare beauty and “hanging” engraved in golden characters above the temple of the Ka’ba in Mecca. Such literary texts, already known to the poet Goethe who collected them in his “West Diwan” were songs of memory, roughly similar to the Greek myths and perhaps initially to the Homeric poems themselves (where these are considered as sets of initially oral songs that Homer would have “only” systematized) that is, they acted as catalysts for the common memory of a tribe and prevented certain events, including news stories, from being lost over time.

These “Qasidat” that is compositions were handed down from generation to generation, and kept high the name or memory of groups, warrior leaders and princes, who were the first protagonists of the compositions. The poet, who evidently had to be a spokesperson since he limited himself to collecting compositions already existing in the collective patrimony and to versifying them, he performed during the many pagan festivals sometimes accompanied by the sound of the lute.

Musicality remained a feature of Arab-Islamic culture.

Music as Heritage

If the Arab-pagan people used to set their own literary heritage to music, the advent of the Prophet Muhammad amplifies this habit. The poet was repeatedly mistaken for a singer-poet throughout the course of his life and preaching since the prophecy and revelation that descended on Muhammad was transmitted by him in a form not exactly musical but chanted.

Even today the Koran is chanted or recited (rather than sung) and a whole series of singers belonging to the modern Arab music scene (also the famous Oum Kalthoum) are or have been reciters of the Koran before being singers in the full sense of the term Ud, which means “wood”, a musical instrument considered the basic model for all Arabic music.

Musical Characteristics

But exactly what characteristics does Arab music possess, beyond its historical roots? As part of the Arab cultural heritage, music has had different outcomes over time, albeit common origins. As is well known, it is possible to speak at the same time of an Arab people (understood as the Arab ethnos) in the same way in which it is possible to speak of a Tunisian, Algerian, Lebanese people etc.

The migrations and inter-ethnic mixes that have affected the Arab people over the course of their history have brought them into contact with very different peoples, from Berbers to Indians and if on the one hand the fundamental cultural heritage has remained unchanged common substratum, on the other hand, particularistic pressures have impressed their influence so as to generate diversification.

Arabic music today is less homogeneous than in the past and perhaps we would do well to talk about Moroccan music, Algerian Iraqi and so on. What must therefore be emphasized is the geographical factor. The extension in Dar al Islam of a heritage that today is hardly a unifying factor today. All this obviously in the light of an ancient similarity that still exists in theory and in structure.

Musicologists tend to diversify at least 3 musical schools: the first is the Maghribine one, the Syrian-Egyptian one, the Iraqi one and a fourth that can be defined Arab-African.

The characteristics of this type of music lie in the melodic organization and in the vocal technique. There is no hardened system and no concept of harmony. The instruments all play the same melodic line, differing in quantity, ie some instruments play one octave above others below the main melodic line. The notation of the melodic line does not occur in written form, in fact an Arab musician would not conceive of the writing of the staff. The organization takes place entirely through the handle of the Arab lute, which is in fact the most important instrument. From this it follows that the Arabic “notes” all have a different name and are not defined on the basis of octaves.

The main concept of this type of music is the “Maqam” which we can translate as the place where the musical composition takes place. Each Maqam also has its own specificity, its own emotional content, or rather a specific melodic expressiveness.